The MBTA: Still Not America’s Fastest-Growing Transit System

If one is going to claim that a transit agency is the fastest-growing in the nation, one must look at the entire system it operates, not just pieces of it.

A few weeks ago on this blog we challenged the Pioneer Institute’s repeated public insistence that the MBTA has been the “fastest-growing major transit agency” in the nation, a claim that Governor Baker echoed in a February 19 interview on WGBH Radio.

The claim is a bold one and one that is counterintuitive to anyone who pays attention to transit issues here and around the country. The past two decades have seen city after city – Los Angeles, Denver, Seattle, Dallas, Washington, D.C., Salt Lake City and more – either build entirely new transit networks or make large-scale additions of rail or bus rapid transit.

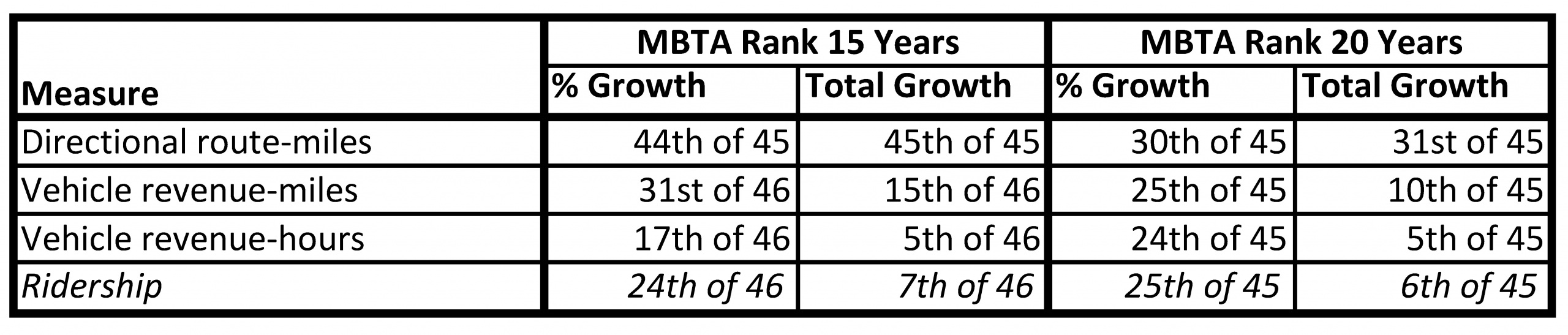

So we put the Pioneer Institute’s claim to the test. We compared the MBTA’s rate of growth against that of other major transit agencies on 12 objective criteria (see table below) plus ridership. By none of those criteria was the MBTA the nation’s fastest-growing major agency, and by some it was among the slowest.

A little over a week ago, the Pioneer Institute published its response to our challenge, which ignored or mischaracterized the bulk of our analysis and instead focused on a 13th measure by which, Pioneer argues, the MBTA can be considered the fastest-growing agency: the number of miles of rail track added since the early 1990s.

Expansion of rail track is not an adequate measure of transit agency growth. It is not even an adequate measure to compare agencies providing rail service. Pioneer’s analysis compares the MBTA against agencies that are unlike it in the types of services they provide, leading to false conclusions. And the distinction Pioneer makes in its response between growth in rail track and growth in rail service is one the institute itself has ignored in past communications with the public.

“Rail” Does Not Equal “Transit”

If one is going to claim that a transit agency is the fastest-growing in the nation, one must look at the entire system it operates, not just pieces of it. However, the Pioneer Institute’s response to our post ignored the existence of buses entirely, focusing only on rail. Had the institute reviewed bus service statistics, it would have found what we documented in our original post, which is that the MBTA provides less bus service than it did in 2000. When all modes of transit are incorporated, there is no question that the MBTA is not the fastest-growing system in the United States.

Miles of Track Is Not an Adequate Measure of Transit Growth

Pioneer’s use of the number of miles of track as its sole measure of transit growth has the effect of propelling agencies that operate longer-distance commuter rail lines above those that provide only urban rail service such as light rail and subway.

Using track-miles as the sole measure to compare the growth of these disparate services is akin to arguing that the MBTA’s commuter rail system is “bigger” than the New York City subway system simply because it has more miles of track[1], even though New York subway trains travel 15 times more miles each year than MBTA commuter rail trains and serve more than 70 times as many passengers. A valid comparison of transit agency growth must include data related to the amount of service being provided, not just the number of railroad ties or miles of rail. This is why it’s usually a good idea not to rely on just a single measure of growth.

Apples to Oranges Comparisons

We discussed last week the problems with using simplistic, blanket comparison between the MBTA, which provides a full range of transit services, and agencies that provide only some of them, such as MTA NYC Transit and San Francisco’s MUNI and BART, which do not operate commuter rail. Pioneer’s response to our post suffers from many of those same problems.

If the Pioneer Institute wanted to compare the growth of agencies that are unlike one another – providing differing services to different types of metropolitan areas – an easy way to do so would have been to compare their relative (percentage) growth over time, as we did in our initial post. Pioneer rejected that approach. It could also have compared changes in transit service across metropolitan areas, providing a fair comparison between cities with multiple transit agencies and those with a single dominant regional agency like the MBTA.

But Pioneer chose not to do that either. Instead, the institute focused on a single measure that relies on a distinction between expansion of rail track and rail service with little meaning in practice and which the institute does not appear to have thought important until now.

Inconsistent Definitions of Commuter Rail “Expansion”

There are two commuter rail agencies in the United States that, by Pioneer’s own admission, have seen a greater addition of commuter rail route mileage since the early 1990s than the MBTA: the Los Angeles-area Metrolink system and the Northern New England Passenger Rail Authority, which operates the “Downeaster” service between Boston and Maine. For the MBTA to rank first in rail system growth, the Pioneer Institute needed to make the growth experienced by those two agencies disappear.

It attempted to do so by suggesting that, because the L.A. and Maine commuter services were operated on pre-existing freight tracks, they do not count as expansion, while the MBTA’s South Shore commuter rail services, which were initiated on new tracks (albeit ones built on pre-existing right of way) do count as expansion.

The distinction is not a meaningful one, either intuitively (if a train track runs through the woods, but no passenger trains travel on it, can it be said to house commuter rail?) and practically, since major capital investments may also be required to launch commuter rail service on pre-existing track. It is also a distinction that the Pioneer Institute has ignored in its own communications with the public.

Earlier this month, Pioneer’s Charles Chieppo wrote on the Globe’s op-ed page that the Big Dig consent agreement “Required expansions [that] included extensions to Newburyport, Worcester, and Plymouth ….” (For the record, the Worcester extension occurred along pre-existing track.) Either the provision of new commuter rail service on existing track is not an “expansion” or it is – the institute cannot have it both ways.

Conclusion

By fair and objective criteria that incorporate the whole of the transit agency’s operations, the MBTA cannot be said to be the “fastest-growing major transit agency” in the United States. The bulk of evidence, backed up by common-sense understanding of patterns of transit growth in Boston and elsewhere over the past two decades, indicates that the MBTA’s rate of growth is far from exceptional.

Clearly, the Pioneer Institute and we have quite different visions of the future of transit service in greater Boston. That is not what is at issue here. We took what was, for us, the unusual step of challenging the Pioneer Institute’s claim in public because it was misleading Massachusetts residents (and decision-makers, as indicated by Gov. Baker’s comments) into believing that up is down – that a transit system that has not completed a large-scale expansion project in nearly a decade and has not expanded the core urban light rail/subway network in a generation was somehow darting ahead of a variety of U.S. cities that have built multiple new rail lines in the race to deliver improved public transit to their citizens.

If the MBTA actually were the fastest-growing transit system in the country, we would be the first to acknowledge it. For some, that ranking – if legitimate – might actually be seen as cause for celebration. But it is simply not the truth.

[1] The MBTA commuter rail network covers 671 track-miles, whereas the New York City subway system covers 660 track-miles, not counting maintenance yards and other non-revenue track miles.

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.