If You Think the Way We Pay for Roads Is Crazy, Just Look at How We’re Paying for Cars

A system that results in many Americans being almost literally shackled to their vehicles for the purpose of extracting high-interest debt is far from ideal.

Congress, as you may know, has been stymied for several years now on the question of how to pay for transportation. At issue is the roughly $13 billion annual gap between what lawmakers want to spend on highways and transit and the revenue coming in through the gas tax.

The sums of money being debated on Capitol Hill, however, are chump change compared to the $420 billion Americans spend on net each year on motor vehicle purchases, according to the Consumer Expenditure Survey.

We’ve documented how the way we pay for roads has been changing, with ordinary taxpayers – not those who drive the most miles – assuming more of the burden. But the way we pay for cars has also been changing in ways that have deep implications for consumers, our transportation system and the overall economy.

First, though, a quick refresher on car financing. For most Americans, owning a car is still a necessity – it is simply too difficult to access jobs and other opportunities without one. So, borrowing to buy a car is in some ways like borrowing to go to college: it can open the door for greater income and opportunity. But while having a little bit of auto debt can be a good and necessary thing, having a lot of it is unquestionably bad: cars depreciate quickly in value and car loans tend to carry higher interest rates than mortgage or educational debt. It is no surprise then, that most analysts recommend that consumers limit their exposure to auto debt and choose auto loans with relatively short (four years or less) terms of repayment.

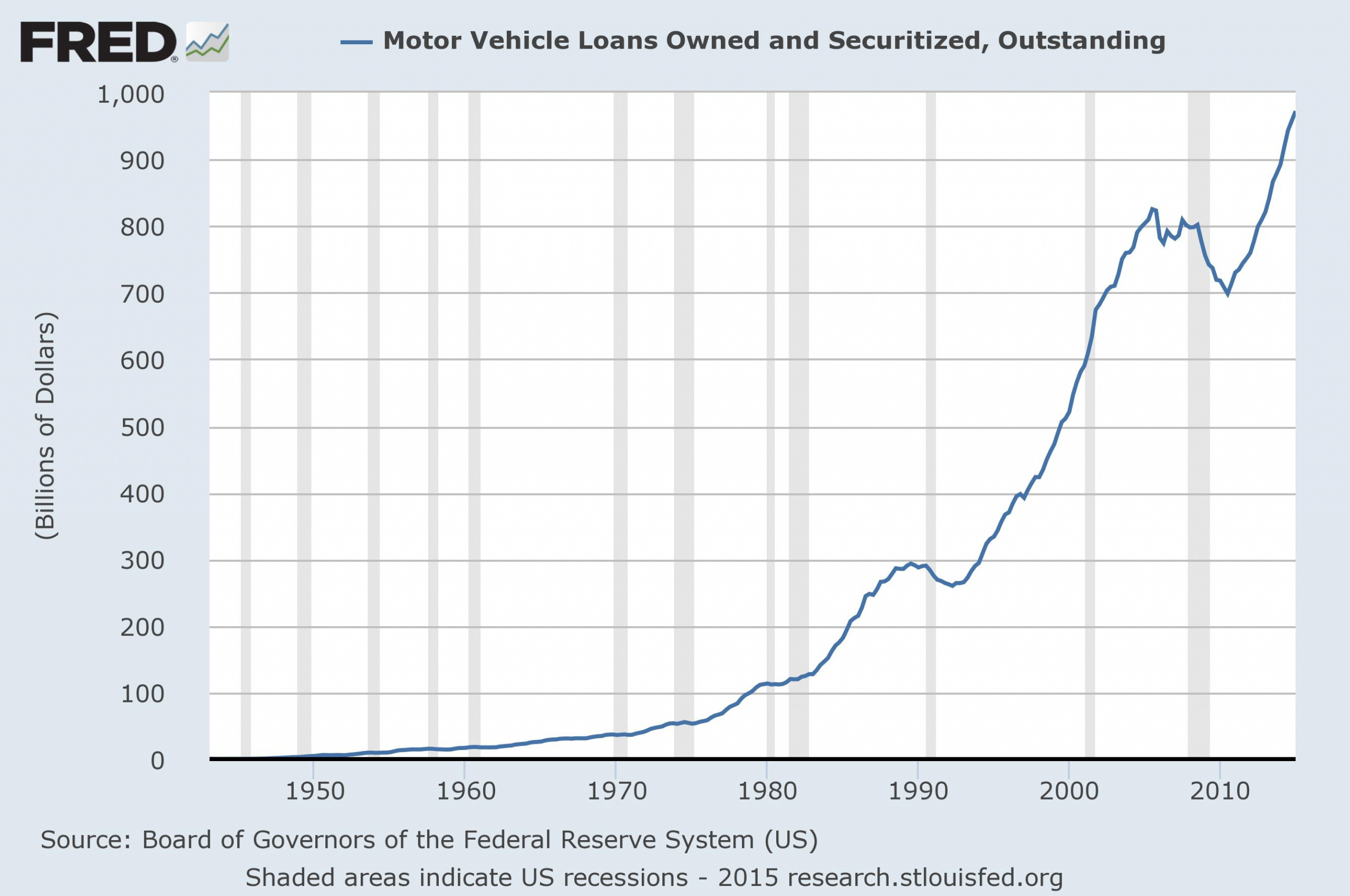

Of late, however, consumers – egged on by car dealers, finance firms, and Wall Street – have increasingly done the opposite, racking up record levels of car debt. According to the Federal Reserve, the amount of outstanding, securitized auto debt jumped by nearly 9 percent over the last year and is closing in on the $1 trillion mark. (See chart below.) Along with student loan debt, auto debt is helping to drive the growth of non-mortgage indebtedness, with the average amount of non-mortgage debt held by mortgage holders increasing by nearly 6 percent over the last year.

Data from Experian (PDF) show just how far the auto finance market has drifted from the traditional conception of good practice:

- The share of new car purchases that rely on financing (as opposed to cash sales) has increased from 77 percent in the first quarter of 2010 to 85 percent in the first quarter of 2015. More than half of all used car purchases now rely on financing as well.

- The average amount being financed and the average monthly payment are both increasing.

- The average term of new and used car loans now exceeds five years and is continuing to increase, with nearly 30 percent of new car loans being issued with repayment terms exceeding six years. Extending the term of a loan has three effects: 1) it lowers the monthly payment, enabling consumers to buy more car than they would otherwise be able to afford; 2) it increases the amount of interest paid over time; and 3) it increases the likelihood that, in the later years of a loan, a consumer will find him- or herself “upside down” – that is, owing far more on a car than it is worth.

Let’s pause on this last point a moment. I have personal experience with the upside-down phenomenon: when my stepfather passed away a number of years ago, he owed $13,000 on a car that was worth only $7,000, the result of having rolled over the outstanding balance of previous car loans onto his current new car loan. As the executor of his estate (such as it was), I was able to simply send the keys back to the lender without fear for my credit rating or ability to purchase a car in the future. Had he lived for another few years, Bill would not have been so lucky.

(Scenes from a bike commute. Dorchester, Boston, MA, USA)

As it turns out, Bill would have a lot of company in the Upside Down Club today. In fact, due to rollovers of previous loan balances and financing of “add-on” products like extended warranties, an increasing number of car loans are upside down from Day One. According to the Office of Comptroller of Currency, the average loan-to-value ratio of a used car loan is now 137 percent – that is, consumers are borrowing 37 percent more money than their car is worth, akin to taking out a $411,000 mortgage on a $300,000 home.

Over the last year, both the Office of Comptroller of Currency and the Center for Responsible Lending have raised concerns about the implications of auto lending practices, especially in the subprime portion of the market, which, according to Experian, accounts for 11 percent of new car loans and more than a third of all used-car loans.

From the perspective of Wall Street, though, the rise of auto debt might not be as worrisome as the housing bubble that preceded it, a bubble that was also fueled by securitization of debt on Wall Street. First, because today’s cars last longer and are of higher quality, resale values four, five, or six years down the line might hold up better than those of previous generations of cars, making the lengthening of loan terms appear more reasonable.

Second, lenders have far more immediate recourse to missed payments in the auto market,in the form of repossession, than they do in the mortgage market. An increasing number of lenders – especially those in the subprime sector – are taking matters one step further by equipping cars with auto shutoff devices that enable them to disable a borrower’s car almost the minute a payment is missed. Miss a mortgage or rent payment and you might find yourself in an eviction or foreclosure proceeding months or years down the line; miss a car payment and you might not be able to get to work tomorrow.

Needless to say, however, a system that results in many Americans being almost literally shackled to their vehicles for the purpose of extracting high-interest debt is far from ideal.

And somewhere down the line, the music has to stop. Consumers may find themselves unable to get new loans for their next vehicle, or be forced to roll negative equity into new loans, eventually throwing the brakes on new-car sales in future years and undercutting households’ financial stability. Investors may run out of appetite for increasingly risky car loans and pull back the reins, again putting the brakes on vehicle sales. Today’s debt-fueled surge in auto purchases could come to be seen as a temporary “sugar high” – not the beginnings of a new normal.

In addition, while this is admittedly speculative, there may be at least a slight connection between the debt-fueled auto sales boom and the recent, low gas price-fueled surge in vehicle travel (the “Driving Boomlet”). New cars tend to accumulate mileage faster than older vehicles, and it is not irrational to think that having access to an expensive, top-of-the-line new vehicle would encourage some drivers to take an extra spin or two that they wouldn’t have taken in their old, beaten up 2004 Camry.

So, there is good reason to wonder whether the recent boom in new car sales is sustainable. And the rise in auto debt serves as yet another reminder of how the transportation infrastructure and policy choices America has made since World War II – choices that have led to almost total dependence on the car – continue to constrain the opportunities of millions of Americans today.

It is too soon to know whether the rise in auto debt represents a “bubble” and what will happen when and if it bursts. But it is not too soon to recognize that our transportation system increasingly locks Americans into choices that constrain – rather than enhance – freedom and economic opportunity. The need for more and better pathways out of automobile dependence for more Americans is increasingly critical.

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.